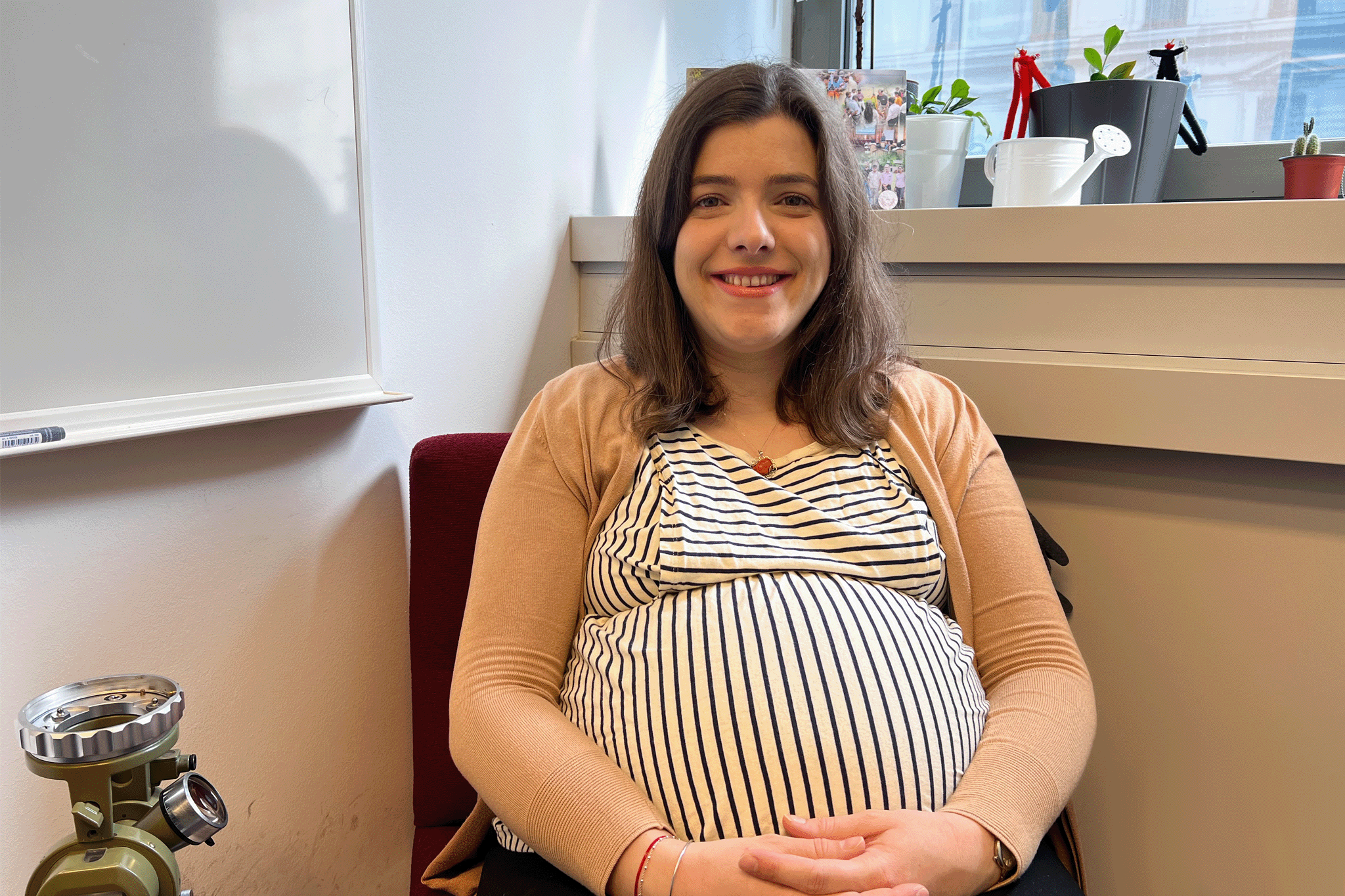

Interview with Jelena Gabela Majic

Autonomous platforms are promising helpers for us humans. They can be used instead of ourselves in areas that are dangerous or simply inconvenient for us. In her research, geodesist Jelena Gabela Majic, postdoc at the Department of Geodesy and Geoinformation is developing algorithms that make autonomous platforms safer. In this interview, the scientist and mother-to-be* who was born in Split, Croatia in 1992, gives an insight into her family background, her research and talks about the situation for women and parents in research.

What do you like about your job?

Jelena Gabela Majic: I love my job. It is very challenging as the problems you deal with are always changing: you have teaching where you get to interact with many different students, you have different research projects, collaboration with other scientists, travelling for conferences, writing different publications, etc. Intellectually, I find it very fulfilling. Academia is really nice as it offers you flexibility in your work day. I am also very lucky to have always worked in amazing teams and that I have always had supportive superiors. That really helps with liking my job.

What led you to your studies and your research subject? Is there a family influence?

Jelena Gabela Majic: My father is a construction worker and my mother works in a supermarket. They worked really hard to raise us three siblings. I guess I always had inclinations towards something technical. My mother built into me love towards mathematics, and my father used to take me to his construction-sites (safe ones of course) and I loved when he would give me little assignments. When the time came to choose gymnasium, I decided to go to a mathematical gymnasium and for university education, I really wanted something where I can apply my mathematical knowledge. I liked geodesy so I went on to study geodesy and ultimately get a PhD in that area.

What do you focus on in your research?

JGM: I specialise in navigation, estimation theory, sensor fusion, positioning in challenging environments such as indoors or in cities, where you cannot rely on GNSS (global navigation satellite system) – most people know about GPS, which is one of them. Basically, I work on the algorithms that have potential to help pedestrian navigation using smartphones, to help drones fly safely and to help autonomous/automated vehicles drive safely.

Where will "Husky" take us humans?

JGM: Let me explain our “Husky”: It is an autonomous platform, a type of robot that is bound to move through its environment independently – and we have developed it at TU Wien. These platforms are extremely promising for us humans. We are still working a lot on Husky – therefore, Well, it is a bit early to say for Husky how far we get with him but specifically as we are still working a lot on him. But autonomous platforms like platforms like Husky have great potential for us humans:. Firstly, for example, it has potential to improve the quality of life for disabled people. Autonomous platforms also have potential toSecondly, they help through delivery of different goods, urgent medicine or medical assistance. Further, Tthey can be deployed in areas that can be dangerous for human life. We want to use our Husky in tunnels for example. Autonomous platforms could be used in caves, mines, search and rescue missions that are often dangerous for rescuers as well, etc. We have also already seen many examples of use of autonomous platforms for monitoring of war zones without risking human life. Of course, you have more selfish benefits as well, like being driven to work by your own car, sometime in future.

Let's talk about a beautiful and at the same time challenging topic: you are expecting your first child. What thoughts go through your mind when you think about motherhood and your professional future?

JGM: I cannot say I am not worried about my professional future. Academia is already challenging enough for everyone, when it comes to getting a tenured position. An extra layer is added once you become or are on your way to become a mother. Clearly, I will not be able to work whenever I want and as much as I want, which is often required in research and science. I was very nervous to tell people at my job, especially since I was between contracts at the time. As I already said, I have a great team and my boss is really supportive so that was not an issue for me. I am very lucky in that regard. As a postdoc, I also have to apply for self-funding, which can take me to my tenured position at an university. Luckily, in Austria but wider as well, funding agencies take into account the fact that you have become a mother and do not penalise you for it. For example, if you are eligible for certain funding six years after PhD completion and you have been on your one- year -maternity leave so seven years have passed, you will still be eligible for that programme. There are many other support systems universities themselves offer to you. Still, it is a fact that the progress of your career will slow down once you become a mother.

43 per cent of mothers leave STEM professions in the 4-7 years after the birth of their first child, compared to only 23 per cent of fathers.* What would you wish for from society and your employer so that you can continue your career path without disadvantages?

JGM: Academia is tough enough even without children. It is very challenging to stay in academia since there are only few tenure positions offered. This means that you often have to move between cities and even between countries for job purposes if you want to stay academia. As a postdoc, you often live from contract to contract and you have no job security because of that. My husband and I have, what is often called a “two body problem”. Both of us want to stay in academia and we are aware, that at some point, one of us will probably have to leave it. I can completely see how so many leave academia after they get the first child because that is the time of your life where you want to stay in one place because of your baby and you also want job security that is so hard to find in academia. I wish that universities were more open to offer tenured positions to good researchers and teachers so that good people do not have to leave academia out of frustration of living from contract to contract. For now, I have no plans to leave my job and have full support of my family and boss.

And finally, what would you like your husband to do in his new role as a father?

JGM: We have seen from other female academics what it means to be a career driven woman with children, and how good of a support system you need to succeed. As I said already, I am very lucky in many regards and I have a very supportive husband who is ready to “slow down” his career as well if it means I continue to do what I love. We approach all of our decisions like partners and with full support of each other and we do not plan to start making changes once the baby is here with us.

Thank you for the interview!

Jelena Gabela Majic was born in 1992 in Split, Croatia. She studied Geodesy and Geoinformation in her hometown at the University of Split (Bachelor 2014), her Master's degree she completed at the University of Zagreb in 2016. Together with her husband, who is also a geodesist, she then moved to Australia to write her doctoral thesis in engineering at the University of Melbourne. After both had completed their doctorates, Jelena Gabela Majic and her partner moved back to Vienna, where she is working on her postdoc at TU Wien.

* Jelena Gabela Majic gave birth to her child between the time this interview was written and the time it was published.

*see “Parent study” commissioned by the Faculty of Technical Chemistry, the Women's Network of the Faculty FemChem, opens an external URL in a new window and the Vice Rectorate Human Resources and Gender at TU Wien. https://www.tuwien.at/tu-wien/aktuelles/presseaussendungen/news/verantwortung-fuer-kinder-maenner-gefeiert-bei-frauen-selbstverstaendlich, opens an external URL in a new window

Interview: Edith Wildmann